Making the Most of Field Trips

I was recently invited to visit the Staffordshire Hoard with Dr Peter Darby and his students as part of the third-year module ‘Anglo-Saxon England in the Age of Bede’. The students responded well to seeing Anglo-Saxon artefacts first-hand. This made me think about my own teaching and how I might use field trips to inspire my students in the future. But the issue all teachers face when organising such trips is: ‘How do I make sure that my students get the most from the experience?’ So, how did the Staffordshire Hoard trip benefit Peter Darby’s students and would I have done anything differently had I organised the trip myself?

The Trip

The trip began at Nottingham Railway Station, where we met at 9:15 to board a train to Birmingham New Street. Once in Birmingham, we had a short walk to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery to view the recently-opened Staffordshire Hoard gallery. For the first 30 minutes, the students browsed the galley by themselves and were quick to try out the museum’s interactive displays, including a giant touch-screen table displaying 3D photographs of the Staffordshire Hoard’s best-known artefacts. When everyone had finished browsing, we gathered together to hear the students give short presentations on items they had researched prior to the trip.

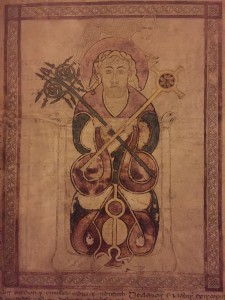

After an hour-long break for lunch, we boarded a train to Lichfield for a guided tour of Lichfield Cathedral. Our tour guide, Dr Robert Sharp, gave a brief overview of the Cathedral’s history, focusing largely on St Chad, the Anglo-Saxon bishop of Mercia and Lindsey. He then took us to see Lichfield’s Anglo-Saxon treasures. First we visited the location of St Chad’s shrine and then we viewed the Lichfield Angel (an Anglo-Saxon sculpture found in the same place as the shrine) and the St Chad Gospels (an eighth-century manuscript containing the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, and some of the Gospel of Luke). After a final round of student presentations, the day ended with a trip to the gift shop.

Outcomes

When asked to reflect on the trip, Dr Peter Darby said:

“The field trip was a success, and I feel that the students really benefitted from encountering some of the material evidence that we had been studying in the classroom (especially the Staffordshire Hoard and Lichfield Angel). Running the trip towards the end of the course meant that the students had a close familiarity with the period and were able to understand what they were looking at. It was also useful for revision purposes, since the items viewed on the day can be cited as evidence in answers in their upcoming exam. The experience of taking the students out of the classroom was absolutely worth it because it helped to solidify an excellent group dynamic. Best of all, the experience conveyed to them that the Anglo-Saxon past is all around them. One problem with running such trips is, of course funding. We were very lucky to have support from the department for this trip, but I would have had reservations about running a field trip which required students to pay (the train fares were about £25 per head), especially considering the considerable financial demands that this generation of undergraduates is under.”

As a spectator, I felt the most valuable aspect of the trip was the enthusiasm it sparked in Dr Darby’s students. The class took pride in their research because they were able to present their findings in the presence of their chosen artefacts. Asking the students to give short presentations was wise, since it helped them to engage with the subject matter and made the trip more informative.

What might I have done differently?

One issue with the presentations was that none of the students brought notes with them. They all recited their findings from memory, which resulted in some fluffing. If I were to host a similar trip, I would ask the students to type up 200 words of notes on their chosen item and bring it with them on the trip. This would not only guarantee that they actually do the research in advance, but would also help to streamline presentations and ensure that those listening gain as much from the presentations as the presenters themselves. The notes could then be circulated as revision aids after the trip.

Another issue was that many of the students chose to research the same artefact, meaning that we heard a lot of repeated information on certain objects (i.e. the sword pyramids) while others (like the millefiori stud) were completely overlooked. In the seminar class preceding the trip, Dr Darby had asked his students to prepare a one-slide PowerPoint presentation on an assigned artefact or building. These included:

- The Lichfield Angel

- Offa’s Dyke

- Sculpture from Repton, Derbyshire including the ‘Repton Stone’

- The Crypt at St Wystan’s Church, Repton

- All Saints Church Brixworth, Northamptonshire

- Sculpture from Breedon Church in Leicestershire

- The Staffordshire Hoard

- The Lichfield/ St Chad Gospels

This meant that the students arrived in Birmingham and Lichfield with knowledge of a range of Anglo-Saxon items. But because only a few of the students focused on the Staffordshire Hoard, some were better prepared for the trip than others. If I organised this trip in the future, I would assign each student a particular item from the hoard to avoid overlap and to ensure thorough research.

Conclusions

The trip was an invaluable experience for Dr Darby’s students and was—thanks to the support of the University of Nottingham’s History Department Alumni Fund—financially feasible. It was also a hugely beneficial experience for me. Above all, I realised that effective forward planning is key to ensuring students get the most from field trips. I aim to put this knowledge into practice in my own teaching. I may even host a trip to the Staffordshire Hoard in the future!

Emma

Some great tips here about making the most of history field trips, especially on the need for careful planning to ensure students get really actively involved and thinking. I agree with your point about enthusiasm as a key learning outcome (albeit non-measurable – though the students do look very engaged in the photo!) and it raises wider issues about the more affective aspects of fieldwork through emotional responses to the artefacts/sites.

Field trips do tend to be popular with students, but the question is why? Cynics might (do) argue it’s because it’s a nice day out and not very challenging. I wonder what the students on the trip felt about the visit? It would be good as a tutor to record something of their experience as that always helps to fine-tune it the next time round. They could perhaps simply write bullet-points along the lines of 3 things they liked; 3 things that might have improved it; 3 things they learned. There are, of course, more complex questionnaires they could be asked to fill in and that you could collect and feed back to them on, either online or in the next seminar.

The tutor on your trip also makes a good point about the value of experiential learning. What do you think fieldwork adds (if anything) to historical thinking that other forms of learning can’t do? Does it get them to pose different questions? See history differently (cf. heritage/non-academic history) or in new ways? Use different learning styles? How does it fit into the notion of contestation that is central to historical argument? And does it lead to a different tutor-student relationship? Hardest, biggest question of all: How effective is it as a mode of learning?

Finally, I wonder if field trips are getting rarer – given costs, student/staff time, organisational headaches etc.?

One interesting point is how use of field trips differs between cultures. See David Ludvigsson’s 2012 essay on ‘student perceptions of history fieldwork’ in a Swedish context where he also reviews the general field (of history fieldwork), categorises fieldwork into its different forms and provides a case study (in D. Ludvigsson, Enhancing Student Learning in History: Perspectives on University History Teaching (Uppsala Press 2012). This volume is freely accessible available online at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:741902/FULLTEXT01.pdf

I know I’ve raised more questions but that’s because your blog really got me thinking about what place fieldwork should have in a history degree programme.

*If anyone would like to make a short 2-3 minute film clip of themselves talking about their use of field trips that would be a great addition to the Historians on Teaching site. We are short of discussion of this aspect of teaching .

Emma, I’m glad to read about your thoughts on field trips. I think you’re right that students always get enthusiastic from field trips and that’s a valuable thing in itself. In addition, I believe that experiencing historical space may help students to understand history in new ways. Also, meeting physical remains and sites help to make history seem real.

But it’s a common problem that it’s hard to take notes when you’re standing and walking, and then much of what’s being said and seen may be difficult to remember. One practical possibility (apart from preparing them beforehand as well as talking through key points when you meet for the next lecture or seminar) may be to prepare a handout that they can use. Of course, your idea that students themselves prepare presentations can help quite a bit.

For further ideas about history field trips, please check out my article “Student Perceptions of History Fieldwork”, available in fulltext at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:741902/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Sounds like a great field trip. I have always been surprised that field trips are not a required part of History degrees in the UK. I have been running an overseas field trip to northern Italy for the last 22 years, but that is organised through Geography where such trips are a compulsory part of the overall degree programme.

Longer trips (mine is one week) allow the students to develop skills during the trip, especially to realise that teamwork is essential to the effective collection of research material. So, were I to organise a day trip like the one you describe I would make sure that students were preparing in pairs rather than as individuals.

I agree that there is no substitute for studying anything first hand, especially if considerable study has been undertaken before the field trip happens, as in the Anglo-Saxon one and as in my Italian one (which is the culmination of the module it is part of).

One other important benefit is that staff and students tend to bond in different ways when outside the normal classroom space.